By Dale Leorke and Aramiha Harwood

The Future Play Lab’s annual Play About Place Symposium returned for its fifth iteration, this year held at RMIT’s Melbourne CBD campus and coinciding with Melbourne International Games Week in October 2023. Its theme was the “playable campus”, with talks, workshops and playable installations exploring how creative placemaking and experimental game design in public spaces can make university campuses more inclusive and resilient.

The symposium opened with a keynote by Dale Leorke and Danielle Wyatt, who discussed how examples of “playable libraries” from their book The Library as Playground might translate to the playable campus, followed by a Q&A with Lab director Troy Innocent. The symposium then involved two hands-on workshops where participants were invited to reimagine and rebuild RMIT’s Bowen Street as a space for play, interaction and reconnection with nature, Country and place using LEGO. Both workshops had about 18 participants, most of whom were women or non-binary.

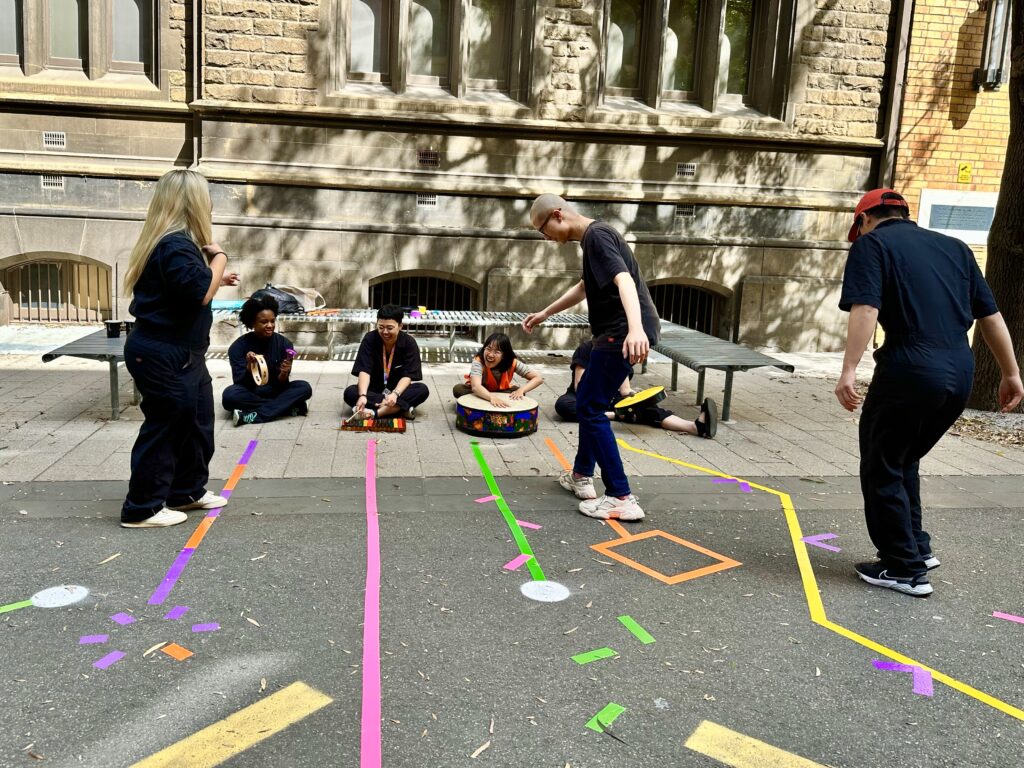

Alongside the symposium, five playable installations created by students in the Lab also ran across the RMIT campus, putting these ideas into practice.

Playable Campus as a Living Lab

The first workshop was co-facilitated by Innocent and Lynda Roberts, Senior Advisor in Creative Communities at RMIT, along with Leorke, Wyatt and Prof Lisa Given, Director of RMIT’s Social Change Enabling Impact Platform and Professor of Information Sciences. In this workshop participants were invited to recreate Bowen Street – an internal street that runs through the heart of RMIT’s city campus and serves as a corridor between two busy roads at each end – based on how they think it should look in one year’s time.

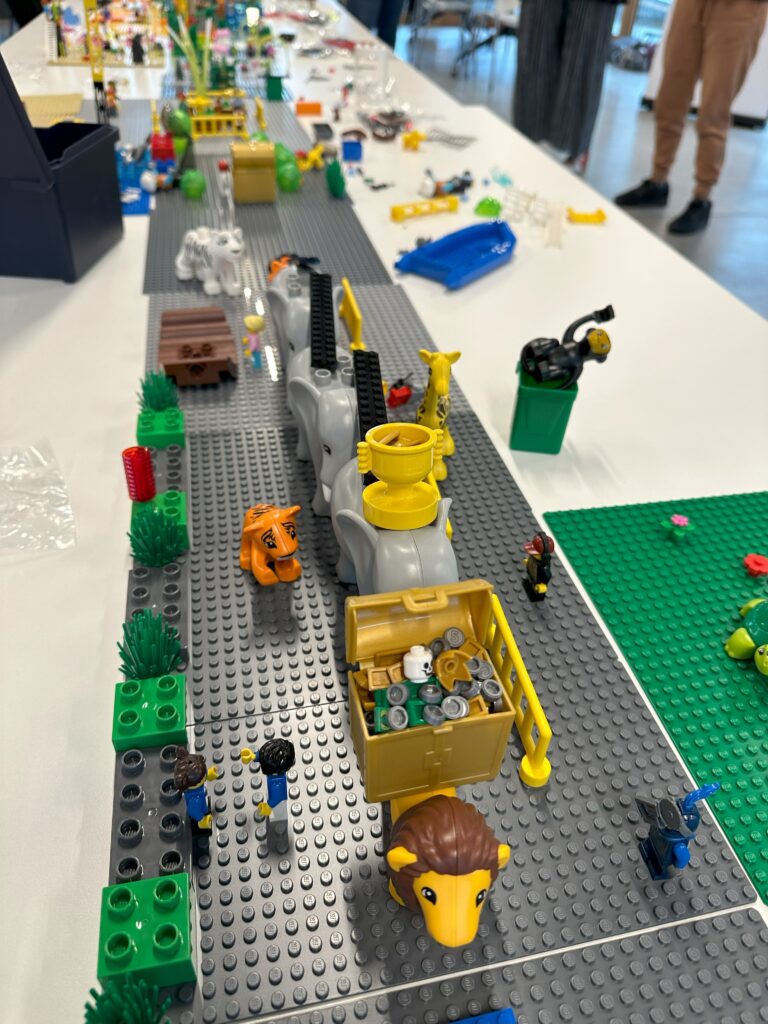

Several rectangular tables were joined together with LEGO baseplates at their centre to provide the “canvas” on which participants would recreate Bowen Street. Participants tended to stay at one section of the table and contribute various LEGO pieces to build up the campus’s infrastructure, buildings, outdoor furniture, public spaces, and – of course – people. Others focused on curating their own “mini-sections” of the campus, some of which included a graveyard populated with skeletons “for the ‘under’ community to meet and discourse”; two “daredevil stations” connected by a tightrope, a drone-racing course and climbable animal bridge with rewards at their end; a rave site for “nighttime activation”; a Holocaust memorial “for reflection but also private alienation if you want get away from the fun of Bowen Street”; and a shark-infested reimagining of nearby Melbourne City Baths.

Although, as Innocent sarcastically acknowledged, “not all of this will be possible” to create by next year, it did prompt a rethinking of RMIT’s campus around “thresholds” of entry and how these thresholds might invite its surrounding community in: “Why would someone from outside the university come if they’re not a student? For knowledge, to learn something, or discover something, or experience something.” The discussion that followed focused on how universities might encourage this discovery through playable installations. As game designer Hailey Cooperider put it, “you’re changing people’s default relationship [with Bowen Street] from ‘thoroughfare’ to something to dwell or engage with. And the great thing about play spaces is that they can create that moment of liquidity in people that allows them to shift their relationship.”

For Roberts, these issues spoke to “the future of the university” itself: “on one level, they’ve become more like businesses and there’s often a paywall to knowledge” but at the same time RMIT city campus is “a very public porous space and that makes me think about how you make RMIT’s knowledge equally public. How do you invert the university in this space through the dwelling points, as points of invitation and exchange?” This might happen, one participant suggested, through “easter eggs embedded in the environment itself, like geocaches or QR codes that spark curiosity.” Another noted that universities “tell stories already” and “we can use that wisely” by making people “aware that the university also holds an interest to people that use imaginations.”

Regenerating Place through Indigenous Ways of Being

The second workshop was led by N’arweet Prof Carolyn Briggs AM, Boon Wurrung Senior Elder and Elder in Research at RMIT. She was joined by facilitators Dr Christine Phillips, Senior Lecturer in Architecture and steering group leader of RMIT’s Architecture and Urban Design Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Engagement Committee; and Dr Aramiha Harwood, postdoctoral researcher in the Future Play Lab.

This workshop again asked participants to recreate Bowen Street, although this time based around the campus’s natural landscape and geography before European colonisation – where a waterway once flowed through its centre – while responding to the campus’s present relationship with its surroundings. Innocent suggested that the opening of a new railway station in Carlton, to the north of Bowen Street, could redefine how the northern buildings of the RMIT city campus connect with the main campus. At the south end of campus, meanwhile, there could be stronger connection with the hustle and bustle of Melbourne Central and the State Library, linking them via RMIT to the shops, cafes and museums of Carlton in the north.

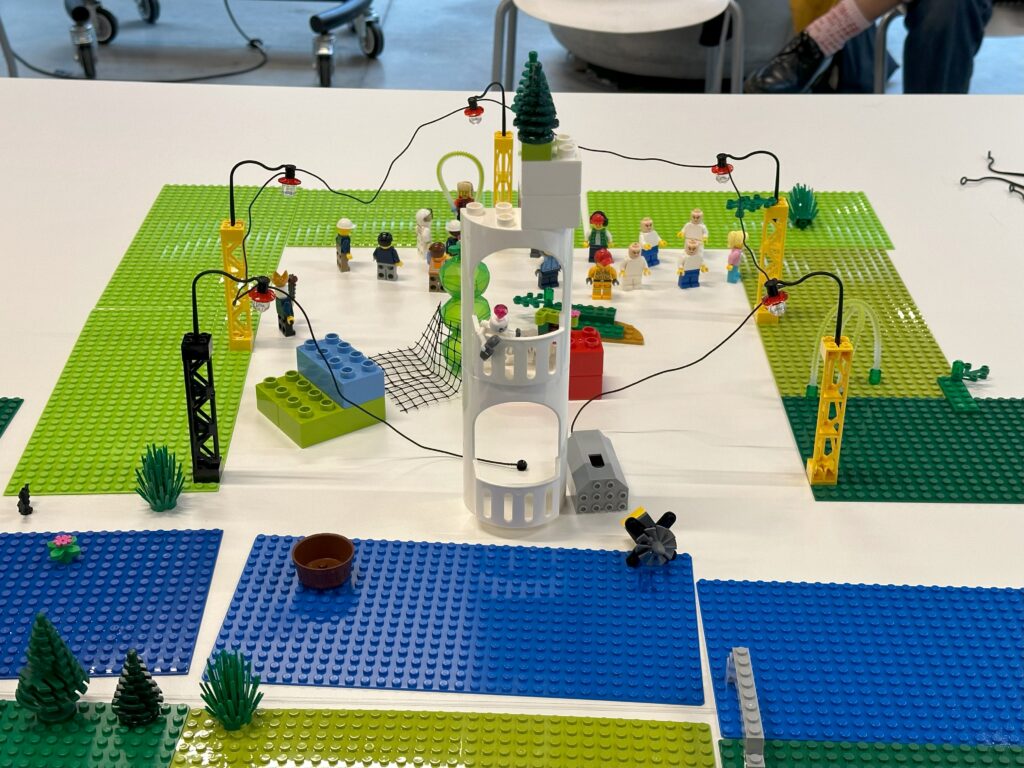

In contrast to the wildly fantastical designs the previous workshop produced, this workshop was somewhat more measured and grounded. One participant requested that a Google Maps satellite view of Bowen Street be shown on the screen, and participants then assembled the LEGO baseplates to replicate existing buildings, open spaces and parks – although with Bowen Street reimagined as a river. Instead of people, the campus was predominantly populated with native plants and more-than-human creatures which had largely been driven out by urbanisation, such as turtles, bats, spiders and insects. An outdoor stargazing zone was set up with beds for people to lie down on and observe the night sky, while a separate community space was established for human gathering and sociality.

In this way, Place or Country could be a pedagogical tool – working as a mnemonic device to help learners remember important advice and/or knowledge from teachers. Perhaps the design of this northern precinct could incorporate these facets of Indigenous ways of being and knowing? Reflecting this, participants created an Indigenous community garden – which could teach knowledge of medicines, herbs and foods – aligned with cosmological and seasonal designs of the garden itself, in one of the enclosed spaces around Building 57.

The workshop ended with a yarning circle in which N’arweet provided some quiet advice and knowledge of her own experiences around this area of town. At times, when she has needed to be in Carlton, she has felt that the city and the urban landscape – the streets and the built infrastructure – have blocked her travels from the CBD: “my problem was I couldn’t get through. I was trying to constantly weave through a system that blocked my way.” She also felt that the redbrick, working-class exteriors of the RMIT City campus buildings best reflected its working-class origins in the former Working Men’s College, as well as acknowledging the locally accessed clay and materials to make those redbricks.

N’arweet suggested that we take a photo of the final LEGO-made precinct from above, looking down. She said we were making a Map of Country, in our minds and in our imaginations, and it could look like much Aboriginal art that we see in our galleries. This brought home to all of the workshop participants that we were engaged in a Creative project that – while looking into the Future – we honour our Indigenous past. What we are bringing about, through Creative Play, are new ways of imagining and interpreting Place – with the help of Creative Indigenous Knowledges and Practices. N’arweet concluded, “we just got to unlock all that ancient knowledge in all of us. I think that’s one of the things we’ve forgotten to do. We are entities that are made up of so many different influences, but we exist.”

Dale Leorke is a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Sydney and a member of the Urban Play Network. Aramiha Harwood is a postdoctoral researcher at RMIT on the Future Play Lab’s Play About Place research project.