Sat 11 October 2025

by Ashleigh Dharmawardhana & Carlo Tolentino

On a lovely Saturday in October, the Greville St. Library hosted an event to mark their official opening. After 5 years at Prahran Square, the library returned to the Prahran Town Hall – a busy site on the corner of Chapel St and Greville St.

The Greville Street Library is twice the space of the former Prahran Square site and has more book collections, public computers, study areas and spaces for events. One could see the potential importance of this renewed library to the local neighbourhood.

https://www.stonnington.vic.gov.au/Library/Visit-us/Greville-Street-Library

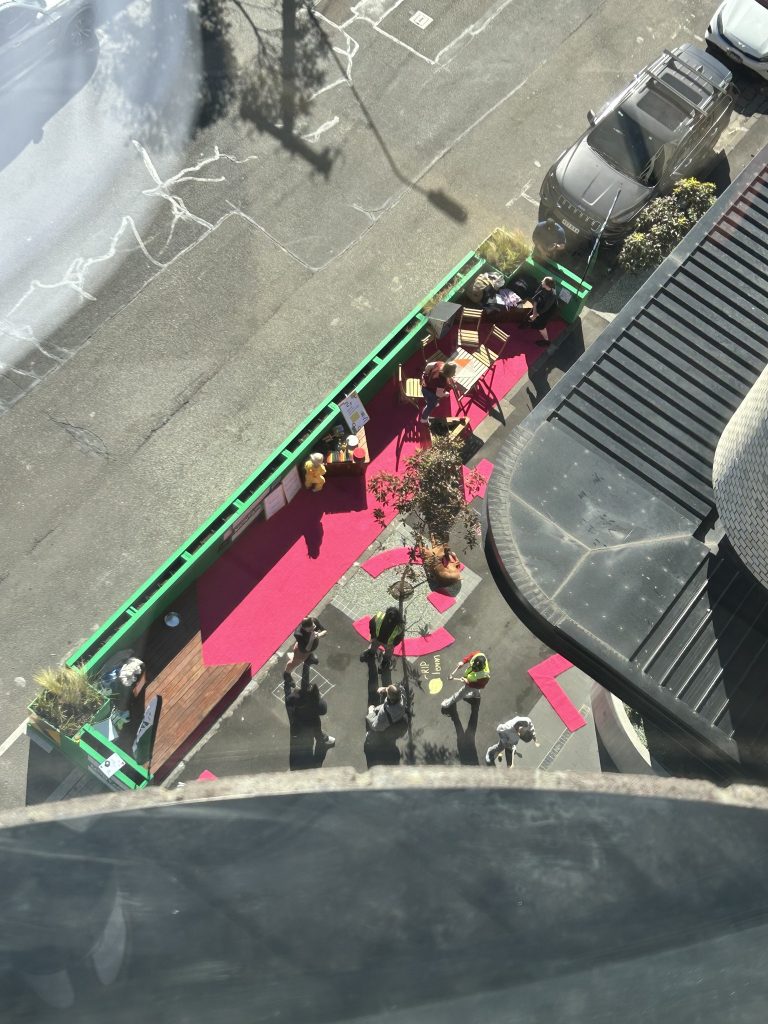

The future play lab were a part of the Greville St Library opening festivities – we hosted a Lego workshop inside, and playbusking outside in the parklet.

The majority of the library opening participants were young families, who eagerly zipped around the site to take part in all of the activities – for instance, there was a reading workshop, boomerang painting session, and collage creating space. Inside at the Lego workshop, approximately 30 people dropped in, and all engaged in creating little spaces that they’d like to see in their neighbourhoods. During the session, we managed to speak to a few adults about the community and their hopes for the space.

Many wanted more spaces for ‘creative freedom’ to create a City of Stonnington where art thrives and people are supported in their creative endeavours. What we also discovered was that the community loves the vibrancy and personality that Chapel St has to offer. Being able to go for a walk, look at quirky shops and boutiques, and see familiar faces at cafes and libraries was cited as reasons they love being in Prahran. In the future, they would like this life to still thrive through ‘more events and more advertising of the events’. One participant remarked how when living in a different city, they felt a lot more sad and isolated because of the lack of community. They expressed that in future, they would like to have more spaces like Greville St. Library, where they can sit down and have a conversation with people passing through – they also shared that the parklet outside is a ‘great place’ to do that. They credit the recent boost in their mental health to moving to Stonnington, and having chances to socialise and feel ‘a part of’ community. A conclusion that can be drawn is that the community are already connected through places like the library, and events that happen here. More spaces like this, more events, and more advertising appear to be the 3 most desired hopes for the future.

The Lego creations were very abstract, and largely shaped by the vivid imaginations of the children who participated. The group began building community spaces – like parks and centres – but ended up with creating mythical spaces, or caricatures of themselves and their families at home and in communal piazzas. Though this didn’t create a cohesive neighbourhood per se, it did reveal that chances to create and engage in shared social activity is extremely valued and generative. The creations came together to reveal that this community wants a chance to create, imagine, and connect, and they want spaces where they can freely do this – as evidenced in the interview snapshots above.

Outside, the playbusking was happening at the same time. A great number of passers by stopped to engage, and the children were extremely enthusiastic – and sad to see us go! The challenging aspect was the space itself – a very narrow strip, with not much separating us from the road. This meant that we had to adapt to the space, and be careful about equipment falling onto the road. Though this was a challenge, it wasn’t a limitation. The crew successfully adapted to the space, and created a fun atmosphere for both people passing through, and people stopping to play. Sometimes they shifted to the side, to facilitate passing traffic. Playbuskers also moved further into the parklet to create more space. It was great to see people smile as they walked by, casually engaged by the very bright and fun space. The participants, particularly the youth aged groups, certainly revelled at a chance to play together under the sun. It can be hard to find spaces to do this nearby, outside of parks and open areas. Having a chance to play next to a community hub, where people come in and out frequently, was indeed valuable. It yields positive results in that play becomes more inviting, community focused, and open to all – many kids who hadn’t known each other began to play, chat, and run in and out of the various other events at the library. Chaotic, but in a fun way!

What this created was a very dynamic and lively atmosphere, which certainly generated a lot of smiles and engagement. It is very apt, given the role of Greville St. Library as a hub for community engagement and activity. It was a great way to mark the opening of the hub, and cement its place in the community as one of life, vibrancy, and connection.